Burying photographs, arranging petals, plants, objects and seeds over images, immersing cameras underwater. The unique way Stephen Gill’s works jumps over the conventional techniques of photography is always very refreshing and surprising. Where and how did his free and fluent imagination come from? We have asked him to reflect back on his journey.

Interview & Text: Mikiko Kikuta

Photos: Stephen Gill, Mengzi Zhang

3 key details from his childhood

In 1971, Stephen Gill was born in Bristol. His interest in photography started at around the age of 11. Reflecting back on that period of time, he told us, “I always had so much energy and so many ideas, but I wasn’t very good at school. There was a note passed on to my teachers that said, “Stephen Gill is not allowed to sit next to the window in class” because I would be constantly looking outside.” Three key details seem to emerge behind the reasons why this restless, yet curious boy became so attracted to photography. The first one is nature and his fascination with it.

“Observing nature, animals and pond life was the first step to understand myself. You know how children love going into the world of insects, of birds, into the microscopic world. I think it’s because you can just dive in and swim freely in that world. By admiring nature with a heightened curiosity, I discovered a world where I could immerse myself. It was like going into that special frame of mind.” As a young boy, by playing with insects, birds, and plants, he realised that new discoveries may not necessarily be about the untouched realms of nature, but also existed in places surprisingly close to us. He found a parallel world where the rhythm and the rules of life are different from those of humans’.

The second influence was his father who loves photography. “He taught me the foundation of photography. It wasn’t artistic, it was 100% technical; how to use cameras, how to make your own developer and process film, how to make bromide and c type prints all by the age of 15. This was an amazing education for me.” The techniques he learned in his childhood became one of his valuable strengths in his practice. “Because I had fully understood the cameras and the materials, I only had to think about where I was going with photography.”

The final keyword is music. Some of his works reflect the close relationship between Gill and music, like “Audio Portraits”, in which he asked members of the public with earphones if he could make their portrait and asked them to offer the title of the song and artist that they were listening to, or “Warming Down” for which, he pasted original prints of his photographs on old classical musical scores. The experience that led to this love of music also goes back to his childhood. “My parents had this record player and I have a very strong memory of watching the inner disks spinning for an extended time. The labels on the records at that time used beautiful solid colour inks: orange, green, purple, electric blue… I was listening and watching at the same time. It was a very strange experience, almost hypnotic.” No one, not his family nor his teachers, not even the young Gill himself, knew that the collision of these three fascinations, guided by his pure curiosity, would make him the artist that he is now.

From descriptive photography to “Hackney Wick”

His desire to become a photographer started when he was helping out local photographers while attending secondary school at around the age of 13. When he turned 16, he finished education and started working in one-hour photographic labs in Bristol. “At 17, I became less interested of developing other people’s films. I remember feeling strongly that I wanted to make my own work full time.” He always liked creating artworks, working with collages, drawings, pen and ink, and letterpress but photography was always at the core. “It’s probably because I was always attracted to photography since I was very young. I loved the processes in the darkroom. It may also be because it gave me a voice. I could articulate myself clearly with photographs.” Gill then started his foundation course in photography at a local college in Bristol. “I was lucky because there was one particular class, every Friday, that introduced different photographers’ work. Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, Duane Michals… it was an hour long and showed about 20 slides. It was very interesting to see how many people explored photography as a medium in very different ways.”

In 1994, 22 years old Gill, moved to London and started an internship at the Magnum’s London office. He was not there as a photographer but helped with the practical and technical tasks such as developing films. He reflects back to that time, that to have been able to see first-hand images of many subjects including the world’s conflicts and social problems, allowed him “to learn a greater understanding of geography and history”, which he enjoyed very much. On the other hand, that was also the time when he started to question photography. “This questioning was a positive experience for me. I was able to recognise aspects of photography that I didn’t really trust or relate to.” The internship lasted for 1 year, thereafter, he was employed for another 2 years at Magnum. He decided to go freelance in 1997, as he “couldn’t stop wanting to make work full time.”

Back then, along with his personal work, Gill did commissions to earn his living which constituted mainly of editorial portraits for weekend magazines such as “The Guardian” or “The New York Times”. With this income, he financed his personal works.

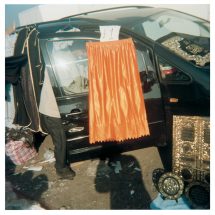

At that time, Gill was hectically making many series staging East London. Back then, his work was a collection of different variations about one theme, just like a typology. It was very descriptive and observational. When he started “Hackney Wick” in 2000, it was his turning point. “East London was overwhelming, and I had too many things that I wanted to do. “Trolley Portraits” a study of people pushing trolleys, or “Audio Portraits” of people listening to music, were more like an entrance point for me and they allowed me to start to grasp subjects that I wanted to explore. As I became more mature and confident, I became less scared of the visual noise of the city. In “Hackney Wick”, it became less about “looking” for things to photograph that were already forming in my mind, but more about “reacting and responding” to what was happening within the geographical parameters. I could feel the energy that radiating from the ground of Hackney Wick.”

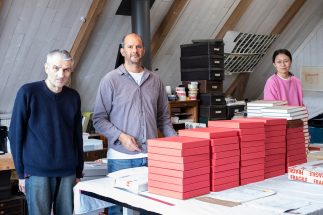

Starting up his own publishing label, Nobody

“Hackney Wick” was published by Gill’s imprint, Nobody which he founded in 2005. Stephen made lino cuts for the cover and endpaper maps that were silkscreened on the clothbound cover and the inside covers of the book. These photobooks had a handmade feeling to it, very unusual at the time, and became very popular. Why did he start his own label at this important time of his career, when he was just starting to get on track?

“In 2004, “Field Studies”, which included 8 series that were created in London, was published by Boot. The format was inspired by a book that I used to love when I was in primary school, “Pond Life”, which was a guide to the microorganisms, insects and amphibians living in ponds. I wanted to use a similar language for this book although all of my photographs were from the human world. People who were lost, the back of the advertising billboards…. This project was completed, but when I ask myself if the book encapsulated the precise spirit of the work, I wasn’t so sure. I like the book but as an object, perhaps it does not fully marry with its content and that’s a sad reality.”

The changes in the publishing industry was also perhaps a push that lead to self publishing. “From about 2000, many things changed. Publishers were able to print more books, but sadly, the overall quality was often affected as speed and volume seemed also to take hold. Designed using Apple computers, they may be visually pleasing, but in my opinion at the time, started to suffocate the book object. What you see on the monitors and what you feel with your hands and eyes are two very different things.” To fulfil his simplest wish as an artist, to make a book that goes hand in hand with the works, he knew he just had to do it himself. “It was the protection of the work. I always felt the need to protect it. Sometimes, I feel like I might even have been overprotective. Especially when I was younger, my work was “everything”. It’s where much of my energy and emotions were channelled. I suppose I still take my work quite seriously even though I don’t take myself that seriously.”

With Nobody, there was a strong determination to move away from the conventional methods of bookmaking. It was decided that a designer would only come on board at the very last stage when all the edits were fully fixed. “By making dummy books, selecting the images and thinking of the sequences, I could feel my hands and eyes synchronising. And I repeat this process, changing and making, to the point where I can say to myself, “This is it!”. For “Hackney Wick”, I concentrated on how the photobook itself, could be a work on its own.” It is safe to say that this earnest wish has come across to the audience. The second book, “Hackney Flowers” was also extremely well received as well, and the following “Buried” became immediately sold out after its release.

Merging the ideas and the techniques

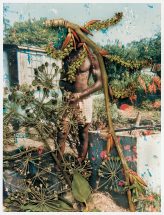

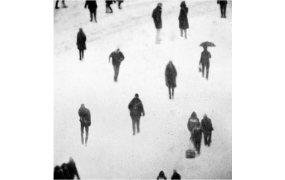

He went on with his practice with East London still at the heart of his work, however, he had also started to explore other locations. Perhaps “Coexistence” was the work that consolidated his refined combination of ideas and techniques. This work was made when he participated in an artist-in-residence in Luxembourg, in 2011. Where he resided, there was a pond that was originally used for cooling molten steel until the late ’70s, a time when the local steel manufacturing was still thriving. “Before going there, I planned the concept for about 10 months. I knew I mostly wanted to extract the images from the pond itself. The problem was, how do I do it?” It required a very complex process for which he had drawn up a plan, something very unusual for him. “I had this image of weaving many different strings into a tapestry. I was thinking a lot about how to show the microorganisms living in the pond, though different in scale, with the same image language as the human world.” This concept is also reflected in the title, “Coexistence”. The idea of the work was about pulling the visuals out of something you can’t see, the parallel world inside the pond. As he loved looking into microscopes as a child, he knew the existence of the extraordinary extent of tiny lives in pond water. With the assistance of the University of Luxembourg, he was able to use their medical microscopes for this project. He also wanted an aspect to the series featuring the people living in the area to be part of the work. However, this pond was off limits for safety reasons so he had to work around it. “Instead, I decided to take the pond to them and got a bucket of pond water. I then started to build the pictures by first, submerging the camera in it and used it to photograph the people. Afterwards, I immersed the prints from that time again, under the same pond water.”

London to southern Sweden

In 2014, Gill moved with his family, to the south of Sweden, his partner’s hometown. Was this change of environment, moving out from the city, London, where he spent 20 years and which was a place undoubtedly, of deep inspiration for his works, not a big risk for his practice? “There is really nothing around this area. Unlike in London, there is no constant flow of visual information. I knew, even before moving here, that my imagination would certainly have to work harder as not much was presented on the surface.” He apparently had also decided to change his way of working. “At the end of my life in London, I was exhausted of sitting at a computer. I wanted to move away from computers as much as possible and work with my hands much more again.”

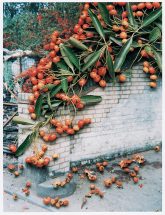

After starting his life in Sweden, he felt the presence of another world, absent during the daytime. “At night, a different world comes alive. In daylight hours I would see traces of life and feel the presence of an active nocturnal world. It was intensely busy, but invisible to the eye.” This feeling triggered the idea of extracting images from the night, which led to the series, “Night Procession”. He set up an infrared camera in the forest at night and programmed it with a motion sensor that activated the shutter. “While I was sleeping, the birds and animals made the images themselves. I found it fascinating. During daylight hours, I started to envisage the movements of the animals. Thinking, “if I was a deer, I would go drink water there.” And when I actually set up the camera, I composed the empty rectangle in the viewfinder, seeing the animals even before they were present.” In addition, Gill felt the need for the place to be fully involved in the making of the works. He also wanted the subject to dictate the colour palette, so he created prints from the pigment extracted from plants. “While I was making this series, the studio was filled with the smell of trees. It was imperative that nature could have an authorship in the image making process.”

His latest work, “The Pillar”

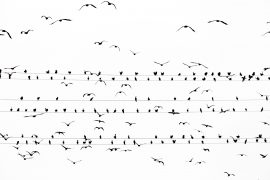

Gill has just released his latest work that he has been working on for the past 4 years, “The Pillar”. “When I moved here, I was very surprised by the vast open land and the big sky. Looking up, I saw occasionally the birds in flight but most of the activity in the sky was simply diluted in the vastness. I was thinking about how can I pull the birds from the sky downwards, just like a funnel. That was the first step of “The Pillar”. I went to the farmer and asked if I could drive two pillars at the edge of his land. The land is immensely flat and vast, and I thought if a bird was going to fly by, it would look like a good place to rest.” On one of the pillars, he placed a camera that gets triggered when it detects sudden motion. To his surprise, many birds started to come to the pillar immediately. The number of different birds and the variety of their movements were astonishing. “Most of the images were simply beautiful. Some of them were more humorous. It was as if they also had human emotions, some even reminded me of my human friends.”

At a glance, these two photobooks have the same format and seem like a continuous series. Gill described both projects that they evoked as if “in a way, the birds and animals made the work themselves. I’ve just orchestrated an environment in which the pictures can be born. For my previous works, I was trying to step back from my role as a photographer. But with these two series, it was as if I had almost finally managed to step out altogether. This was a very positive thing for me, and I enjoyed it a great deal. Actually, the pillar is still there. I can’t stop, it’s like an addiction.”

Lastly, we asked him if he had any advice for emerging photographers. “Hmm…What I have been doing up until now, is to consider my work as my most precious thing and to protect it. Even if you question yourself about your ideas, trust your original instinct and see things through. You have to remember that the most important thing is that you feel happy with it yourself and perhaps, never think of an audience during the making of the work.” Recently, Gill was asked, “do you think you are successful?” For many people, success is perhaps measured with money or fame. “In that sense, I am definitely not successful at all. However, to have been able to make the work that I love for the past 30 years and to have the freedom to respond to my ideas and follow my instincts, is a huge success to me. There’s something I tell young photographers very often. There are people who have power in the photography world. It’s fine to show them your work, but please be careful and see the great potential in rejection, and not always think, “I want to create a book with that publisher” or “I want to do an exhibition at that museum.” It is important that you remain an individual and you can also bypass the establishment if necessary and do things yourself. This is one of the reasons why I created Nobody. Do not think that they have the key to your future work. It’s all about your own journey and the path you chose and create for yourself.”

Stephen Gill

born in 1971, in Bristol, UK. He held many exhibitions at galleries and museums such and has works in the permanent collection such as. The Victoria and Albert Museum (London), The Museum of London, and the TATE. The books he publishes from his own publishing house, Nobody, are highly praised internationally. He now lives and works in Sweden.