Text by Dal Chodha

Is it the pose that makes a fashion picture? Maybe it is the make-up and hair and nails? Is it defined by the texture of a pavement or the colour of a wall? Is it about the clothes? The works presented here by Hugo Comte, Thomas Albdorf, Feng Li, Valeria Herklotz, John Yuyi, Campbell Addy and Jet Swan are technically fashion pictures because they have been made mostly for the commercial context of a magazine, billboard or advertisement, yet there is something else going on. On their own, either yanked from the spine of a magazine, or as they are here (single jpegs on a screen), these pictures perform in a different way. They exist as fragments of an attitude. A frame of mind.

Fashion is a strange mix of nostalgia and impertinence. The conventional belief that a fashion photographer’s trade is to freezeframe a buzzy moment into something that will only last a single month has become undone in an age where all pictures outlast their welcome. They don’t go away when a billboard is replaced, or a magazine trashed; they languish online forever. And so, in reaction to this permanence, the creative generation making work today unanimously try to avoid the uncomplicated label of “fashion photographer” – instead preferring looser, more ambiguous terms like “artist” or “image maker.” The disciplines of fine art, creative direction, graphic design, sculpture and photography have collided to form a more changeable discipline. The business of making pictures takes more than the click of a button.

Hugo Comte studied architecture in Paris before pursuing photography. He dedicated months to researching fashion editorials from the 1980s and 1990s to understand what had been made before him. As a result his own glossy work channels a kind of nostalgic hero-worship; its composition, lighting and attitude is from a previous epoch. The closeness of Comte’s pictures to the iconic body of work produced by Steven Meisel between 1996-2001 makes them almost pastiche, except, Comte’s is so tightly observed that they trick the modern eye. Comte refers to himself as an “image-maker” rather than “photographer”—his influence presides over all aspects of the image, not just the final frame we see.

Berlin-based Valeria Herklotz makes photographs that are informed by her previous experience as a model scout. Her work is discussed, introduced and framed more as portraiture than straight photography. The Chengdu-based Feng Li was—or perhaps still is—a “street photographer” and more recently has become a “fashion photographer”. What it means to become a fashion photographer is a topic of discussion that more editors and photographers should be asking themselves. The South-London born Campbell Addy is a “photographer and filmmaker” but his richly toned work, focused often somewhere between the Black body, cultural identity and queerness, feels also like a political and curatorial act. He told British Vogue that his “culture” is a “hyphen.”

After working for several years as a Graphic Designer and Art Director, Vienna-based Thomas Albdorf’s photographic sculptures—mainly still life—take their inspiration from artists Fischli & Weiss, Roman Signer and Koki Tanaka. They bring together attitudes and processes previously reserved for the art gallery. If you were to ask him, Albdorf is simply an “artist”. The Taiwanese Chiang Yu-yi (who is known professionally under the moniker John Yuyi) is a “visual artist”. The British-based Jet Swan is modestly a “photographer.”

There has been a redefinition of the term fashion photographer to something more elastic, which suggests that photography—and more specifically fashion photography—has become too narrow a term. There is an invisible line between the function of Albdorf’s absurdist and surreal constructions deployed to sell handbags and shoes and purses and their formal conceptual contexts for example. Born in Linz, Upper Austria, Albdorf studied Transmedia Art and so has been focused on the contemporary status quo of the photographic image and the decontextualization triggered by internet distribution.

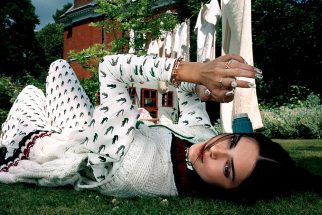

John Yuyi’s work is shaped by the internet too—it is a kind of revulsion of her own online addiction. A pre-or maybe post-internet attitude shapes her pictures that are layered and memeable. They involve human skin in a way that goes beyond make-up—there is a sense of collaboration and commodification as faces and bodies appear in the pictures more than once. They are refracted and replayed in a number of ways. Her practice explores aspects of social media, and her own hefty online presence.

The process of making pictures has been changed by how we now live our lives online, but how has it changed their content? In Comte’s work, the internet influences a knowledge of the archive and what has come before. Often, Comte’s photos look like they are from the 1990s when they flick up on Instagram. Herein lies their appeal—they are familiar, comfortable. They maintain the hierarchy of glamour and grunge and sleaze that so much of contemporary fashion photography is based upon. “90s images really express an energy more than anything; some eras it’s about style or concept, but this specific era was about expressing a human energy,” Comte told i-D in 2020. His photos have a metallic din, skin is very precise in texture that it is almost cyborgian. His photos reflect the glow of the screen; faces are lit with a gentle radiance.

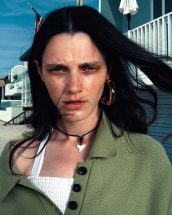

Valeria Herklotz makes pictures that feel like today in part due to their vivacity, energy and simplicity. The women in her pictures are often young and caught mid-pose. They are de-glamourised. Her taste in clothes—which is something we need to always remember when looking at fashion photography—is dishevelled, layered, not quite right. With her work she is tugging at traditions of portraiture.

Location is central to the fashion image. When we leave the safety and anonymity of the studio and take to the streets, we can more easily capture a clearer sense of time. Based in the Chinese city of Chengdu, Feng Li’s work takes a more playful, less Eurocentric idea of beauty and has some fun with it. His pictures have life and vigour. Fashion photographs made in Europe that claim to be inspired by movement often feel very still, very posed. Li’s photos are wild with smiles, arms flying, feet askew. They radiate a happy, idiosyncratic charm. The clothes he shoots are extreme too and are given equal status in the gestures of the models. They get the performance they deserve.

That Li began as a street photographer is key to his practice and approach. He took up photography in 1996 before securing a civil service job working as a photographer for the Sichuan provincial department of communication. That job involved photographing technological hubs, high tech factories, and CEOs. His fashion work needed to be the antithesis of this, for his own sanity.

I have been thinking about which of these images look like now. This is an absurd feat but nevertheless it is the primary function that fashion pictures need to serve. Campbell Addy’s lens always seems to luxuriate in their subjects; women and men are strong and bathed in colour and light. Addy’s work borrows the classism of the 1950s studio setting but jolts it into the now with an unabashed reverence for queer glamour.

Jet Swan’s body of work has a perversity to it that feels like it could only exist today too. There is always something off or surreal or ugly in her pictures which seems to puncture any preconceptions we have about a woman making pictures that are adjunct to or informed by fashion. Swan’s debut monograph Material gathered together three years’ worth of photographs and portraits she had made of strangers. A lot of her subjects are rarely identifiable; their heads cut off and their bodies exposed. There is a rawness in the work that is confrontational. She presents the female body in its truest and most multifaceted way. Never airbrushed perfect, in fact, Swan seems to highlight the bumpiness of skin, the outline of the body, the push and pull of veins.

Her pictures prove that to us that any sort of demarcation between the disciplines of fine art and fashion photography is futile. What we need to consider is the content of all of these pictures and what they might tell us about fashion today. In Swan’s work, we are perhaps over fashion, drained by its excesses, its lies, its fantasies. Her work seems to feel like now because it is grounded in an inky, earthy truth.

Dal Chodha

London based writer Dal Chodha is Editor-in-chief of Archivist Addendum – a publishing project that explores the gap between fashion editorial and academe. He contributes to various international titles including Modern Matter, AnOther and i-D and is a Contributing Editor at Wallpaper*. Chodha has been working in academic institutions for more than a decade and is Stage One Leader of the BA Fashion Communication & Promotion course at Central Saint Martins.