Text by Giovanna Borasi

Takashi Homma has described his own work as a form of ‘New Documentary’[1].

He captures the present in a straightforward and understated way, picturing what he sees, as he puts it. I often have thought of what he means with the generic and encompassing word ‘new’ in the ‘new documentary’ definition of his work. I think it contains many things, but foremost is the fact that he would approach what he sees in a non-direct way. While architecture is one of his life projects (together with mushrooms, waves, Tokyo, and portraiture)[2] , he has never photographed architecture frontally, in the kind of traditional manner used by many others to document a building. He captures architecture and its form, power, and value using a way of picturing that is indirect, oblique, mediated by the life in and around it.

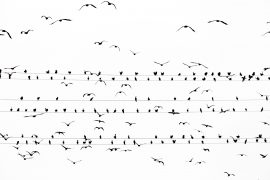

In Homma’s short movie In a Morning[3], featuring the Geoffrey Bawa-designed hotel Heritance Ahungalla (former Triton Hotel) in Sri Lanka, we discover Bawa’s architecture, spatiality, and materiality through the capture of the systematic labour of the hotel staff cleaning thoroughly, early in the morning, the hotel compound. Not only this, but the sound was captured live, so we ascertain the site’s vicinity to the ocean (long before seeing the two direct shots of the beach, coming respectively midway and late in the 4m20s film) and appreciate the natural tropical environment the hotel is embedded in; we could imagine the smell of the place, seeing people collecting fallen flowers from the ground; we could feel the coldness of the meticulously polished cement floors, seeing the workers moving, almost skating, around it in bare feet; we understand the beauty of the different colours in the palette, with the black bases chosen by Bawa for the many columns… Bawa’s architecture is there but it is not alone. And we even wonder if in fact the movie is more about ocean waves, dogs, birds, trees, flowers, and labour, with Bawa’s architecture just happening to be the backdrop, or the place that connects and holds together all these other phenomena.

High Court Portico, Chandigarh, India ©︎ Takashi Homma

In a similar way, in the video High Court Portico, Chandigarh, India, commissioned to Homma by the CCA and featuring the High Court building by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh[4], we never see the entire building, but we perceive its function and the power it channels in seeing just one part of it. The striking contrast between the colored walls and the many judges and lawyers dressed in formal black, yet captured on break in front of the building, chatting among themselves, laughing, twirling their moustaches, delivers a very different and very human portrait of an architecture otherwise commonly portrayed in its imposing dimensions as one of the main institutional buildings of the Capitol. We can appreciate how the building and its outside spaces are in fact used, instead of seeing the architecture austerely empty and fiercely concrete. Furthermore, the sound is not the diegetic soundscape, but an Indian pop song, hyperbolizing the juxtaposition between the loftiness of the architecture, costume, and program, and the humanness of the individuals playing their roles in this theatre.

Somehow, I think Homma’s ‘new’ refers to a new, more humanistic way of seeing. And as he pictures what he sees, he allows us to see in the same way.

Tokyo and My Daughter @ Takashi Homma

In his previous work and book Tokyo and My Daughter (2006), this approach is again very present. Images of architecture, the city (Tokyo), and the daughter (in fact a friend’s daughter) are all collapsed together in a sequence that evokes both the city and, especially, the way the kid is living in it. We imagine those spaces to be the background and the context of her life, and we wonder how the city reflects in her and how she, growing, reflects the way the city is growing. The many spaces might not even be the spaces she lives in, but we understand the atmosphere of the city she’s growing up in, and we would not understand the fabric of the city in the same way if we weren’t seeing her in contrast with views of the neighbours. In his movies or photo series in books, Homma seems primarily concerned with life and with how architecture holds the moments of it together.

On Homma’s Instagram account, the series with the hashtag #mymother (this might really be his mother, not like the kid in Tokyo and My Daughter) also inadvertently conveys the city of Tokyo, mainly its interiors. Here again, architecture or interiors are not the subject, and so in a very indirect way we discover the intimacy of these spaces only through the intimacy of the way Homma sees his mother in them.

In general Homma does not seem interested in the way his images or moving images are circulating, and he is using all kinds of different support mediums, from books, to magazines, to prints, to Instagram shots. Also, he is not frozen in a specific photographic technique or obsessed by any technological aspect involved in producing or circulating his pictures. Homma’s ‘newness’ might lie in his ultimately being interested only in the fact that his images will be seen, or maybe even in “Exchanging only data, rather than physical prints, and [in being] a photographer who doesn’t shoot”[5].

If this comes to pass, to be a photographer who doesn’t shoot, we will be really seeing what he is seeing. Maybe this is the new documentary after all.

[1] “Photojournalism is a mode of documentary photography, but my way approaches the documentary slightly differently. Somebody once referred to my approach as a private or intimate documentary, but the phrase new documentary suits me well”. From oral history filmed for the 2023 CCA exhibition The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project. Takashi Homma, “New Documentary. Takashi Homma in conversation with Stefano Graziani and Bas Princen”, interview By Stefano Graziani and Bas Princen for Canadian Centre for Architecture, December 2022.

[2] Takashi Homma, In a Morning. Casa Brutus, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybWa-nH3iXo

[3] Homma, “New Documentary. Takashi Homma in conversation with Stefano Graziani and Bas Princen”.

[4] Takashi Homma, High Court Portico, Chandigarh, India, 2013. Digital video, 07min 10s. Commissioned by the CCA © Takashi Homma.

https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/75609/to-see-what-the-architect-saw

[5] Takashi Homma, “Photographer Takashi Homma on Bach, punk and working with ‘no preparation’”, interview by Sophie Galdstone, Wallpaper.com, 27 July 2022.

https://www.wallpaper.com/art/takashi-homma-through-the-lens-profile

Giovanna Borasi

Borasi’s work explores alternative ways of practicing and evaluating architecture, considering the impact of contemporary environmental, political, and social issues on urbanism and the built environment. She studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, worked as an editor of Lotus International (1998–2005) and Lotus Navigator (2000–2004) and was Deputy Editor in Chief of Abitare (2011–2013). She has been Director and Chief Curator of the CCA since January 2020.