Text: Diane Smyth

“I think if I had sat at home ten years ago and thought ‘OK I’m going to show how Britain’s brilliant and how diverse it is,’ I never would have left my kitchen, because it would have been too overwhelming,” says Jamie Hawkesworth. “It was really very simple, I just enjoyed going out and exploring.”

We’re talking about his new book, The British Isles, which mixes portraits, landscapes, and incidental images and was mostly shot in Hawkesworth’s own time, on trips he made around the UK. He shot it from 2007-20, a tumultuous period in British history roughly stretching from the credit crunch to Covid, by way of the Brexit vote in 2016. A referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, Brexit proved highly divisive and kicked off an ongoing, highly contentious debate on immigration, citizenship, and nationalism. You wouldn’t know this from Hawkesworth’s images. Instead, The British Isles is a gentle look at a particular time and place.

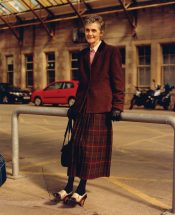

There’s a rainbow shot over a damp landscape, a bustling high street, the sunny side of a building. There’s an old-fashioned pram laden with candyfloss, a loaf of bread, even a puddle. And then there are the people, who are a wide variety of ages, and come from a wide variety of ethnic groups and identities. There’s a smiling, stylish older lady at a train station, a Jewish boy flying a kite, two young black men with tall hairdos, and a middle-aged white guy in a suit, waiting at a bus stop, squinting at the camera. At the end of the book there’s a shot of the photographer’s own boots.

They’re diverse, but that wasn’t something Hawkesworth sought out, either when he was shooting the work or editing it. He just photographed so many people it turned out that way, he says. He adds that he didn’t set out with any agenda or opinion in mind, about Britain or anything else; The British Isles doesn’t have an introductory text or essay, or even any picture captions. “I like to think there’s space around each portrait,” he says. “There’s enough openness for people to think different things.

“I just really enjoy taking peoples’ pictures, and also going to a place and not knowing what I’m going to come across,” he adds. “I would turn up at the train station and, nine times out of ten, just pick a place that looked nice on the board.”

And if that sounds like highly subjective, it is. Hawkesworth is enormously successful, but he doesn’t make big claims, either for himself or for his photographs. The period 2007-2020 was pivotal, he agrees, but it just happens that that was when he was shooting – he got into photography in 2007 when he was at Preston University, after originally opting to study Forensic Science. The British Isles includes three of his earliest images, three black-and-white shots of young Asian kids in a neighbourhood he walked through to college. He was trying to use his Mamiya RB67 handheld, he laughs, so all but these shots were blurred.

The next 13 years saw a meteoric rise in his career, including shoots for clients such as JW Anderson, Loewe, Vogue and Fantastic Man, and exhibitions at venues such as Huis Marseille in Amsterdam, Red Hook Labs in Brooklyn, Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo, and The Hepworth Wakefield in the UK. In 2019 he published a book with Joan Didion. The most recent images in The British Isles were shot for British Vogue, for example, during the first Covid lockdown in 2020; they show essential workers such as ward sister Eunice Ouko, train driver Narguis Horsford, and shopkeeper Jatin Patel and family.

But again, you wouldn’t know this from The British Isles. Most of the images in the book are personal but the commissions don’t stand out; Hawkesworth doesn’t think of his commissioned work differently, he says, because he tries to take only commissions he cares about. The British Isles also includes a photograph of the environmentalist Isabella Tree shot for The Gentlewoman, for example, her back turned and a rainbow above her head. It also includes a photograph of a girl dressed in cobalt blue, made with the stylist Benjamin Bruno for Man About Town in 2011. It’s the only fashion image in the book, but he’s included it because they street-cast the girl, and because it helped kick-start his fashion career.

Somehow, whether he’s shooting a kid with an ice cream or an Autumnal tree, Hawkesworth’s images consistently look like his. It’s something he learnt from Dan Burn-Forti, he says, a photographer he assisted in London early on. Their styles are worlds apart but he was impressed by Burn-Forti’s eye, how he could go “from photographing a portrait of a chef or the Prime Minister or a yoghurt or bananas or whatever” and always convey his humorous, quirky world-view.

“Dan would really embrace the awkwardness of someone or something, and because of that I started to appreciate the strange and funny things in life,” Hawkesworth explains. “Those things you’d normally walk straight past, I started to like their quiet surrealness.”

Hawkesworth’s style is also down to some very particular choices though, choices he made early on. In the 2000s many photographers were being pushed into digital, working with laptops that allowed others to see what they were shooting; Hawkesworth had just graduated and was looking for work, but even so, decided this wasn’t for him. “Luckily I dug in my heels,” he says, deciding to stick to medium format film and always print his own work. It’s something he does to this day, and he spent the best part of a year printing the images for The British Isles.

This devotion to film meant he initially missed some jobs, but this only spurred him on. If he didn’t have paid work he had more time to shoot his own images, he reasoned – including moving back to Preston for a month to take his now-famous images of Preston Bus Station, printed as a zine with Preston is my Paris in 2010 and as a monograph with Dashwood Books in 2017. If he did have assisting work, he was “so annoyed” he wasn’t making his own images, he’d take a trip at the weekend to shoot. These images then become his calling card, as he’d pair recent landscapes and portraits and email them to people he admired. In 2015, Miu Miu asked him to make similar pairs for its 2015 resort collection ad campaign.

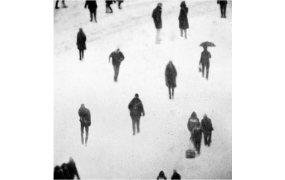

When he got busier with commissions, he kept making his own work, fitting in personal photographs while on location, and taking the whole of August – and later September too – to shoot for himself. Unlike many of his commissions, he could go on these trips on his own; for most of the images in The British Isles, it was just him, his Mamiya, a Pentax round his neck, a tripod, and a bag. “I look at those pictures now and it’s such a nostalgic feeling of just being in the middle of nowhere by myself,” he says. “It’s such a nice feeling.”

It sounds idyllic and was, but it was also hard at times. Travelling to Unst, a far-flung island off the north coast of Scotland, Hawkesworth took a train, two boats, another train, and an hour-long hike, and found himself asking what on earth he was doing; on other trips he’d walk for miles without finding anyone to photograph, and his head would start to sink. Somehow this also turned out for the best, as he spotted interesting puddles at his feet, or looked up and “suddenly saw this amazing landscape”.

“I was in Newcastle, and I’d been walking for ages, and I hadn’t found anyone, and I was sitting on a wall, feeling completely depressed,” he says of another shot. “I looked up and there was this woman and this pram, covered in candyfloss. It was the weirdest, strangest photograph, like something you couldn’t even imagine. It reminded me of what I was doing.”

And what he was doing was really focused on the photography, because his images were ending up in boxes, put to one side while he worked on more pressing things. Eventually a friend asked if he’d ever do anything with them, then Covid struck and he suddenly had time to get in the darkroom with these shots. He ended up with 500 portraits plus the other images, and initially struggled with how to put them together, trying and rejecting a straight chronological sequence in the book. Ultimately he decided to try to evoke how he felt on his trips, keeping open-minded, staying in the moment, and really looking – not thinking about a bigger project, a comment on Britain, or anything else.

“The feeling I have, when I’m going out exploring, is that everything is kind of a surprise,” he says. “It’s that excuse the camera gives you, to look at stuff you would normally just completely miss.”