Los Angeles-based Fumi Ishino first attracted the public’s attention after publishing “ROWING A TETRAPOD” through the photobook publisher MACK in 2017, and is also a participating member of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography exhibit, “Contemporary Japanese Photography vol. 15, ‘Things So Faint But Real’”. How have his 15 years in America – including his time at Rochester Institute of Technology and his photography studies at Yale University – influenced his thoughts on photography? Ishino, who exhibited in the 2016 edition of “LUMIX MEETS BEYOND 2020 BY JAPANESE PHOTOGRAPHERS,” continues in creating new work – taking stock of both cultures with the backdrop of contemporary American photography. What is it that his eye seeks to see?

Interview=IMA

―How did your career get started in the U.S.?

I came to the United States in 2003; after studying psychology at a university in the Midwest, I got a job that had nothing to do with photography. A lot happened after that, and I ended up working as an advertisement photographer’s assistant. At the photographer’s recommendation, I decided to go to the Rochester Institute of Technology.

―I heard that after entering RIT’s advertisement photography program, you transferred to the fine art department. Was that a difficult time for you?

Fine art was very constrictive for me back then. However, I was intrigued by its concepts and how unfamiliar it was. While the advertisement courses offered instruction in the more technical aspects, fine art professors showed me conceptual photography collections and contemporary art. Luckily for me, we had lots of art books and a number of sofas in the college library – I went there often in my free time. I started off by learning about the styles and ways of thinking of several different artists: pondering about what drove them to make these books and pieces of art.

―As an artist working in the U.S., is it important to attempt to articulate the unfamiliar aspects of art?

It can make it easier to analyze work – whether your own or someone else’s – by utilizing language to examine it. When delving into the investigation of history, or context – whether it be their own or somebody else’s ¬– people in the United States seem to attach significance to the act of verbalizing one’s thoughts as part of the process of understanding them. Knowing more about history and context often helps me to escape from my own rigid formulas and structures to develop my practice.

―I would like to ask you about your photobook “ROWING A TETRAPOD,” which was published through MACK. How did you end up publishing with MACK?

I shared my portfolio with a MACK artist who then recommended my work to the publisher. The project took shape slowly from there.

―Did being a member of 2016’s “BEYOND 2020 #4” lead to any exciting opportunities for you?

I learned about differences in context that exist between Japan and America by interacting with other artists my age. Their modes of thinking helped me to understand their contexts more clearly.

"LUMIX MEETS BEYOND 2020 BY JAPANESE PHOTOGRAPHERS #4" Amsterdam Exhibition (Photo: Shinji Otani)

―Did you discover any differences in how people view your art in the U.S. as compared to Japan?

The intention of my work is to consider how one can bring about diverse interpretations from the conflict that arises when incorporating the cultures and contexts of Japan and America. At a recent exhibition, I learned from the audience that even if we are all from different countries and cultural backgrounds, we can uncover new perspectives and feedback by bringing together various peoples and turning a critical eye to the status quo.

―When you’re making something new, do you think it’s better to know whether it’s been done by someone else before?

Personally, I think it’s better to know. I like the process of considering information and ideas, and I think that the amount of information taken in correlates to how much you are able to generate outwards. Even if other artists have done it before, there’s always an opportunity to learn about different viewpoints and ways of thinking from all kinds of art. This gives me a chance to see my own work from different angles.

―What is your impression of how Japanese people are perceived in the United Stated?

I feel like both American and Japanese people are inclined to focus their attention on their own affairs these days. In some parts of the U.S., many think that America can take care of itself without anyone else’s help. Numerous communities are strongly divided; they seem to have lost perspective and acceptance of anything different to or outside of what they know. In Japan, we hear theories about Japan (or Japanese people) turning into an essential version of the “Galapagos Islands” – or becoming increasingly insular from the rest of the world.

I think that there are certain mindsets that are only directed inwards: things kept purely within a circle become exclusive – they do not warrant conversation in the outside world. I think that Japan shouldn’t try to make it on its own, and I feel the same way about America. Moreover, it’s preferable not to be solely preoccupied by one ideology – what’s important is the process of respecting diversity and eliminating prejudice: paying attention to your own world along with the one that exists outside of you.

―Do you have any particular competitions or art book fairs that you would recommend to aspiring photographers?

I recently completed a residency at Light Work (https://www.lightwork.org/) in Syracuse, NY. They have lab spaces for photographers, along with excellent equipment and knowledgeable staff. I think it’s great that they provide accommodation, production support, and artist grants to chosen resident artists. Many of the staff are also practicing artists, so it’s a great environment to exchange insights.

Lab space at Light Work.

―Tell us about your plans for the future. What do you want to accomplish from here on out?

I hope to share my work and ideas with the people I meet. I think that connecting and speaking with people allows us to revisit any psychological barriers we use to distance ourselves from others – such as stereotypes or power dynamics. I regularly set up gatherings at my own studio and at other places where people with interests spanning beyond just art are able to meet, and it’s something I want to continue doing. It’s good to have a place where we can discuss things in a casual setting.

I’m also looking to try out something that lets me reconsider the idea of hierarchies through artwork. Utilizing hierarchies is a shortcut to define or categorize ideas, but I wonder if that always works in any place or context. For example, people prioritize different aspects of photography; like the time in which you make pictures, or how you edit them. Yet there are many cases where one can make seemingly bad pictures into interesting ones by virtue of their size or layout. I think that it is possible to see a totally different side to a work of art by removing the element of “evaluation” – such as how a photograph is said or even thought of to be “unworthy,” – for a moment and placing it together with other things. In my latest work “Melon Cream Soda Float” – now on exhibit at The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo – I used “pop” and “kitsch” in an attempt to render a space where hierarchy has collapsed due to distortions of visual and verbal cognition.

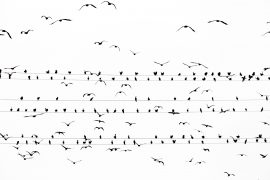

Melon Cream Soda Float, 2017

Fumi Ishino

Born in Hyogo Prefecture, Ishino graduated from Rochester Institute of Technology in 2012 and Yale Graduate School of Art in 2014. In 2015 he received the ‘Japan Photo Award 2015’ and an honorable mention in the ‘Canon New Cosmos of Photography’. In 2017, he published his first photobook, “Rowing a Tetrapod” (MACK). Ishino is part of the “Contemporary Japanese Photography Vol. 15: Things So Faint But Real” exhibition at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum.