The intense shadow and blinding light; the distinct features of Viviane Sassen’s photographs. Having experienced her childhood in Kenya full of vivid colours, studying fashion and photography with those memories at heart and overcoming her father’s death, she brings to life images of beauty but with the presence of Death and Life alongside. Beginning with her most recent work, let us trace back her course of life, and take a close look at her exceptional world which entrusts its full interpretation to the viewer.

Text: Joanna L. Cresswell

Photos: Ayako Nishibori

When construction began on the Palace of Versailles’ exalted Hall of Mirrors in 1678, the architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart was ordered by the ruling Louis XIV to spare no expense; this was to be a space of complete and shimmering opulence, with every part of it symbolising prosperity beyond all imagination. The vaulted ceiling was painted with tableaux depicting the glory of France’s achievements; statues of ivory and gilded bronze were crowded around the periphery; and crystal chandeliers were suspended like ice sculptures, low and heavy in the centre of the room. The mirrors themselves, however – all 357 of them – proved to be a more troubling conquest. Watching as this vision rose up before him, the king insisted that every material in the room should have been made in France, but at the time, the only true mirror-makers were in Venice. The story goes that the Venetian government was so protective of its monopoly on the craft that it had its artisans swear their methods to secrecy, and threatened to assassinate anyone who left to work elsewhere. Nevertheless, on the lure of great acclaim at the Palace, a huddle of the best defected, and after being ushered quietly across the border, they got to work; stolen hands building a thing of almost immeasurable beauty, and building for their lives.

I begin here with this oft-forgotten piece of the Palace’s history because I learned of it while researching into the world of Viviane Sassen and I thought about it a lot as I pieced her life together in the weeks that followed. So many of our great feats of architecture are built on the back of human stories just like this, aren’t they? History has unfolded within them in ways both subtle and significant, but ultimately all that labour and presence disappears like breath on a mirror. Sassen’s most recent body of work, Venus & Mercury, was made at Versailles, and over the course of six months in 2019, she was given out-of-hours access to roam the halls. For her too, it was the untold stories that had the most allure. She read and photographed private letters from Marie-Antoinette to her lover, dug up tales of forgotten women in the archives, and made collages from images of statues, adding washes of colour over their ivory forms. Beyond this, she included real people too – real bodies – in the forms of a small group of young women she met by chance, who were born and raised in the Palace’s shadow; in the town beyond its walls.

When we speak, Sassen talks to me of her time at Versailles excitedly, recalling how her imagination ran wild at the beginning. “It was an enormous privilege to be able to spend such long days practically alone when there were no visitors,” she says. “I was able to open every door, see all the hidden rooms that are never open to the public. I laid down in a small maiden’s bed in the attic, and I stood in the private rooms of Marie Antoinette at Le Hameau.” She felt a really strong energy at Versailles, she says, hard to explain and maybe it was just her imagination, but it felt electric. And as for the Hall of the Mirrors, she was enchanted by it. At one point, she wanted to take a naked self-portrait in there, mostly just because she could. “I made plans to come back another day but I dismissed the idea altogether in the end, for vanity reasons,” she laughs. In many ways, I thought, the image would have fit, because so much of her work over the years has oscillated at the edges of her own self-exploration.

I also begin this piece with mirrors because for Sassen, they have been a consistent and powerful metaphor for what she calls ‘the other world’ since she was young – this other world being a place beyond consciousness, seen while she sleeps or recalled in memories from long ago. ‘They’re important to me because I’ve always been interested in what we can’t grasp, and they allow you to step into that other world’, she said of mirrors once, and later, in regards to the abstract nature of her work, she added, ’I always try to avoid too much context. I isolate these things in order to make them more abstract. My images are like a hall of mirrors; they reflect back at you what you already have inside.’ Sassen, now 48 years old and with 16 published photo books under her belt, has spent a lifetime making pictures from what she already has inside, and her work since, has been of mirror-images and split selves, dreams and nightmares, moments remembered and things only imagined. To find out where that impulse truly came from, we should begin at the very beginning.

Kenya, the “Home” she still dreams of

Sassen was born in Amsterdam in 1972. Her mother was a social worker and her father was a doctor. She has two brothers, both younger than her. When asked, she describes herself as a sensitive child right from the get-go, shy and unforthcoming, with a tendency to lose herself to fantasy, and always with her head down making or drawing something. At the age of two, her father’s work took the whole family to Nyabondo, a small village in western Kenya, and they stayed there until she was five years old. Her father worked at the hospital and there was a polio clinic right next door. So much of Sassen’s early memories are formed around her incidental exposure to the ill or suffering bodies of patients. “I think the fact that he was a doctor has had a big influence on me,” she writes me in an email. “When I was young, I was quite impressed that he was dealing with matters of Life and Death.” I note that she capitalises these two words, and it strikes me as a small but deliberate gesture that reveals the essential weight she places on these things, even in conversation. At dinner sometimes, her dad would talk to her mum about his work, and occasionally, an emergency would come knocking at their front door. “It made me afraid sometimes,” she admits, “and I think it has added to my fear of death as I’ve gotten older.”

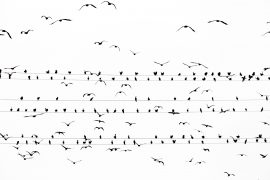

These were formative years for Sassen and she forged a deep attachment to Kenya throughout them. Everything about her memories of that place – “the light, the shadow, the colours, the people, the inky black nights, the starry sky,” she recalls – was imprinted into her mind indelibly. She would dream about it for years after she left. She still dreams about it to this day. In interviews, she has referred to this period of her childhood as her “years of magical thinking”; the ones that shaped her vision and the basis of fantasies she would conjure in her mind and then invent images for in the decades to come. She remembers the day they flew back to the Netherlands for good. “It was night when we arrived at Schiphol [airport]. I saw the lights of the airport and thought all of the stars from the heavens had fallen to earth. For a long time, I felt like I was stuck in a parallel universe that was not my own, and I really longed for Kenya.” There’s that notion of mirrors and other worlds. The trouble with having your life uprooted at such a sensitive age, she says, is the creeping sense of displacement you are left with – she was too young to really remember the Netherlands before she left, and too old not to feel the heartache of missing Kenya when she returned. But going back to Kenya now, as an adult, she’s an outsider: there but not from there, even though she can still conjure memories from there as if they were yesterday. It’s a strange sensation; like an itch she has scratched at her whole life.

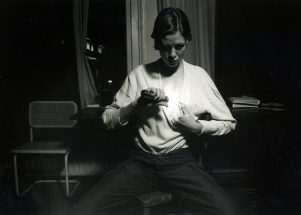

The strength she gained from switching to the other side of the camera

In college, Sassen enrolled on a fashion course before later switching to photography and fine art. She spent those years taking a lot of nudes and self-portraits, exploring her own sexuality and having her first relationships, she remembers. While studying at the Academy of Art and Design in Arnhem, she modelled for the graduate collection of the now very well-known designers Viktor & Rolf, and later, walked in their shows and appeared in films and campaigns as they released their early collections. From there, tall and blonde with wide eyes and a reserved but curious sense of self (she referred to herself in those days as a “shy exhibitionist”), she fell into the world of modelling, and across the next four years, she was photographed by a number of photographers again and again. She quit when she felt she no longer had power over her body. ‘With a man behind the camera, a sort of tension always develops, which is often about eroticism, but usually about power,’ she said once. ‘Power play between man and woman. I found that intriguing for a while, and I even sought it out. But I always found it uncomfortable too. It was never straightforward.’

After that, she focused on the beginnings of a photography career, drawn behind the lens instead. In the early days that wasn’t easy, and she took any job available to her, shooting weddings and events, and taking on droll commissions from corporate outfits. In an interview with the Gentlewoman, she recalls photographing the office buildings of an insurance company all over Holland. “I’d travel to all these cities on my folding bicycle with a map and my camera and shoot these horrible offices,” she sighed. For her, it was means to an end – a way to keep honing her craft. At night she went home and stacked up copies of i-D and The Face, and read everything she could find about surrealism and the shadow. Her interests were wide-ranging, moving between the worlds of fashion and fine art even then. Later, as her work in both realms gained recognition – as she shot campaigns for Louis Vuitton and unveiled shows at the Venice Biennale – she would say that fashion allows her to express her extroverted side; and her personal work, the introverted side.

The Death which cast a dark shadow on her life and practice

The Death which cast a clark shadow on her life and practice when she was 22, Sassen’s father committed suicide. It was a seismic event that fractured the foundations of her existence, and in the years that followed she would find the spectre of it overshadowing her life and slipping into the cracks and crevices of almost all of the work she made (“an undertone of death,” as she described it once). In an interview for the Dutch magazine See All This in 2017, she talked about the day she found out. ‘I was in the darkroom, at the Academy in Utrecht. A workshop assistant came to fetch me. “Your brother called,” he said. “You need to phone home.” He left me alone in his office, which I thought was strange. When my brother answered the phone, I heard him say to my mother, “Shall I tell her?” And then he said it: “Dad’s dead.”’ Just like that. She stood there for a moment, and then she felt outraged, anger swelling within her. She kicked a table leg and paced the room as the wave washed over her. Then, she felt numb. The way she passed the news on to the classmates who were lingering outside was similarly austere to her brother’s delivery. In just ten impassive words, she told them: ’My dad is dead. He fell out of the window.’

A darkroom is a strange place to find out bad news, isn’t it? I ask her in our correspondence. Something about it as a space. I root around on my bookshelf and quote her something the German-American artist Esther Teichmann says about the darkroom being this watery, womb-like space – a place to cry and process away from the world. “I can really identify with that, and now that I think of it, I haven’t spent much time in the darkroom at all since the loss of my father,” she says thoughtfully, and then she recalls a visit she made to the late photographer Lee Miller’s darkroom in the UK two years ago. “Indeed, I got a very strong feeling of sadness while being there, and after leaving, I felt suddenly exhausted. Maybe it’s something to do with suppressed anxiety and anguish after all.’ Maybe so. Spaces do remain within us; and we are able to recall past emotional states when we return to them. That’s the whole basis of psychogeography. And that’s why she has such a draw to the landscapes and the people of Africa.

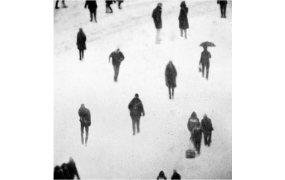

In 2002, some years after completing her degree, Sassen and her husband Hugo embarked upon a trip through various parts of Africa, weaving across the eastern subcontinent and ending up back in the area of Kenya that she had lived in as a child. She wasn’t looking for images on that trip, she says – and by that means she hadn’t specifically set out on a journey to make a body of work – but upon returning there, images began to reveal themselves to her; vivid, dream-like scenes eclipsing in and out of the shadows in this place she had spent her early years. Her very first photobook, Flamboya, which was published in 2008, arose from this initial trip and the images in that series look like hallucinations. Later, in 2011, Parasomnia – a portmanteau of the words paralysed and insomnia – picked up on this thread of sleeping and dreaming, flashing back to a near-death experience she herself, had as a student too. The pictures in this project – of covered mouths and obscured eyes and bodies floating face down in the water – are gorgeous but troubling in an otherworldly way and there’s a tangible, frantic sort of constriction you feel when you look at them.

Sassen said goodbye to her father several days after his death. His body was laid out in his office. She thought he looked terrible, but beautiful too. ‘I went and sat beside him. I rested my hand on his head, and I started talking to him. Then I made a self-portrait, with the self-timer. You can’t see that much in it, just the casket and the flowers really. And me standing beside it. I wanted to be in a photo with him just one last time. After that, it was okay. That was my goodbye.’ When I read these words from an old interview of Sassen’s, I thought about Sally Mann and her photographs of bodies in the morgue; and about David Wojnarowicz and his pictures of Peter Hujar’s body in the hospital just after he passed; feet cold, mouth open, unfaltering love between the two of them. It can be unutterably painful to just let go of bodies and resign them to memories, can’t it? Of course, there’s something latently fetishistic in acts like these – we photograph what we love and can’t keep; what we had and can’t get back. For Sassen, bodies in photographs have always enthralled her; and her images are wrought with the friction. ‘These are the recurring themes in my work: death, the fear of the unknown and at the same time, the longing to merge completely with someone else, in a kind of embrace’, she said once, adding, ‘To not be alone.’

In The Glass Essay, the poet Anne Carson writes of the deep sense of loss and longing that has plagued her across the years. Perhaps the hardest thing about loss, she opines, is ‘to watch the year repeat its days’, later describing this sensation as such: ‘I can feel that other day running underneath this one / like an old videotape—here we go fast around the last corner / up the hill to his house, shadows’. The day Sassen’s father died has remained just so: running under the days she’s had since, and the penetrating power of that loss has shaped her aesthetic vision across the years, manifesting as a quiet but ever-present shadow cast across hundreds if not thousands of photographs. Everything leading up to the 2015 however, was a more gentle undoing, until she made the project UMBRA and finally decided to parse the shadow her father’s death had left.

The changes of Sassen through her motherhood

She picked up copies of books on shadows like Victor Stoichita’s A Short History of the Shadow and looked at Carl Jung’s theories about the shadow and the subconscious, but it all got a bit too academic for her – she is by her own admission, an impulsive, aesthetically-led artist – and so at that point, she threw out the textbooks and travelled inside herself instead. “In UMBRA, I relived my father’s death and was able to process it,” she concluded at the time. It was the final part in a grieving process that had been bubbling up for years.

When asked a few years ago what point she thought she had reached in the development of her work, Sassen said, “I have the feeling that I’m halfway. For me, UMBRA signified the conclusion of the first half. I had no idea what I was starting, but it became a kind of soul-searching journey. As a person, I may have become a little calmer, but also much happier. More settled in myself.” In our last conversation, I ask Sassen where she stands on that question now, all these years later. “Well,” she begins, “after finishing UMBRA I thought ‘I’ve said it all’ and I felt at peace, like it was OK for me to die or never make work again.” Not really, of course, she says, but symbolically, as an artist. What she didn’t know then, is how it would open up new doors to unexpected places and her work would evolve as her life did again. Sassen gave birth to her son, Lucius (“Latin for ‘light’”, she tells me) in 2008, the same year her first photobook was published. Her work and her life always seem to intersect in these ways; one informing or mirroring the other. I ask her what sort of impact motherhood has had on the way she sees her world. “Oh boy, that could be too complicated a question to answer,” she replies but goes on to say that when he was born, “my fears in life vanished for the greater part. I felt a sense of belonging, like I had finally found my destiny.” After UMBRA, she allowed the experience of motherhood to inform where her work took her next. “I started painting on my pictures and making collages, all in a very playful and experimental way; maybe I had finally given my father’s death a place, and maybe it allowed me to be reborn again in my artistic practice.”

In dense and dazzling collages, she felt around the edges of femininity and fertility, and what it means to bear a child. That’s where her photobook of Mud and Lotus came from. “It’s all rather obvious in a psychological way, of course,” she says. “It’s the way you translate these mundane, human themes into your art, and transform them into something meaningful that transcends the ordinary, the cliché. That’s hard work and as an artist, you don’t always succeed.” But if you’re Sassen, you do keep trying. In UMBRA, a photograph of Lucius running along the beach beside Sassen, her shadow blanketed over his small form, works as a small reminder that our own shadows can extend into the experiences of the people we love.

As I was wrapping up this text, I thought of another thing I had learned about Versailles: people say that the scent of the gardens was so strong during the 17th Century that it made visitors ill. Something about the stifling sensory undercurrent to all that paradisiacal beauty seems to resonate with Sassen’s work, doesn’t it? It made me think about the synaesthetic pleasure of looking at her work – the intensity of sensation and feeling that she harnesses with such mastery in her pictures – and what darker parts of her personal history ripple below their surfaces. “I prefer to conceal and go in search of an undercurrent, which people will just have to guess at for themselves. In a subdued, understated way, I show a great deal, and my work is certainly dramatic too, but I remain an aesthete,” she said some years ago. All sorts of shadows can be hidden in scenes too blindingly brilliant, and Sassen knows this well.

Reprinted from IMA 2020 Winter Vol. 34

Viviane Sassen

Born in 1972 in Amsterdam. She spent her early childhood in Africa and later joined the Utrecht School of the Arts and the Ateliers Arnhem to study fashion and photography. She then began her career as a fashion photographer for magazines such as Purple, VOGUE, Dazed & Confused and shot campaign visuals for leading fashion brands including Miu Miu and Louis Vuitton. She participated in the “New Photography” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art New York in 2011. The same year, she received the Infinity Award – Fashion Photography by the New York International Center of Photography. In 2013, she exhibited at the 55th Venice Biennale for the exhibition, “The Encyclopedic Palace”. Her later exhibition “UMBRA” (Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, 2014) was nominated for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize in 2015. Some of her major photobooks are Flamboya (contrasto, 2008), Parasomnia (Prestel, 2011), UMBRA (oodee, 2014), Pikin Slee (Prestel, 2014), Of Mud and Lotus (artbeat publishers, 2017).

Joanna Cresswell

Writer, editor and curator based in London. Specialising in photography and cultural topics, she has written for numerous media and has edited various publications such as Unseen Magazine, Self Publish, Be Happy: A DIY PhotoBookManual and Manifesto and PhotoBook Review published by Aperture. In addition, she has curated a number of projects including those at The Photographers’ Gallery and The Whitechapel Gallery.