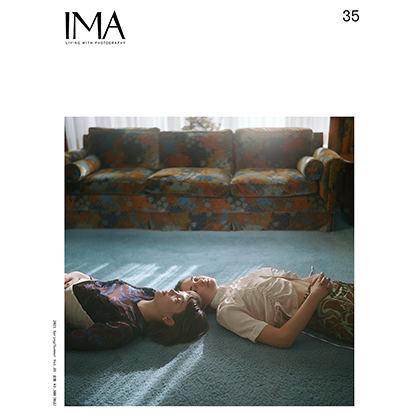

“A dreamy pastel candy girl world.” That’s how American photographer Ashley Armitage, who was born at the tail-end of the millennial generation, recently described the aesthetic of her work. Elsewhere, the New York-based, mid-1990s born photographer Tyler Mitchell presented his vision of a sun-soaked and blissful “black visual utopia” in his 2020 photobook I Can Make You Feel Good. “People say utopia is never achievable,” he wrote thoughtfully in the foreword to his book, “but I love photography’s possibility of allowing me to dream and make that dream become very real.” Japanese photographer Kanade Hamamoto echoes this philosophy too. Born in 2000, she spent her teenage years honing a rhapsodic and imaginative visual style. With her book midday ghost, she wanted to create a “dreamlike world beyond reality” she told her publisher – “a book that allowed people to forget their surroundings.”

©︎ Ashley Armitage

All three of these artists were born into, or on the cusp of, the same generation – Gen Z, which spans those born from the mid-1990s through to 2010 – but what really unites them here is a radical and dazzling tendency towards idealism and immersion. What emerges from the words above is the sense of a shared impulse towards creating not just scenes but whole worlds in their pictures; not just pictures we want to hang on our walls, but ones we want to live inside of. Ones we wish the world were more like now. This is something that ripples out across much of the creative outputs of other Gen Z artists too. But where did it come from?

It’s always difficult to define exactly where a zeitgeist begins, but if we think about the things that seem to unite Gen Z values – progressive politics, intersectional feminism, the belief in the future as a place of limitless possibility, and sexuality and identity as a fluid and ever-shifting spectrum – it must, at least in part, have to do with how young people are growing up now, and where. For the generation prior to Gen Z, the Internet was still very much a novelty in their teenage years, but for much of this generation, what happens online is as much a part of their lives as what happens offline. They are hyper-connected digital natives, their devices are like second limbs, and image-media is intrinsic to their existences.

©︎ Kanade Hamamoto

The internet has democratised and globalised the growing up experience. Young people from all over the world connect every day on the internet, develop communities and hang out in digital spaces across time zones and geographies. The way talent is rooted out and given a platform has changed too, and by sharing their work online, Gen Z artists have the chance to be discovered from anywhere. Whatsmore, Internet aesthetics have fed into the type of work Gen Z makes, with wildly popular platforms such as TikTok and Snapchat leading to digital layering, filtering, blurring and glitching becoming popular tools when making art. And this immediate and nebulous use of image-media extends to the value placed on output too. There isn’t the same preciousness towards print with this generation, for instance – it’s still appreciated, yes, but digital has just as much potential. Where once making zines on a xerox printer was the quickest and cheapest way of getting your work out into the world, now sophisticated and wide-reaching social media portals can offer you that same opportunity as an early-career artist.

We are all products of our times, to a certain degree. Gen Z, in many countries, have had the benefit of a more progressive upbringing than their predecessors – raised to accept more types of diversity than their parents had been, for instance – but they have also seen human rights injustices and political discord play out on the world stage right in front of them, been raised amid swelling economic anxiety, and they will also be the ones to bear the greatest brunt of the impending ecological crisis. This has made them a politicised generation of young people ready and willing to fight for freedoms of expression. As a result, many Gen Z artists use image-making as a force for change, conjuring in pictures the world as they want to see it.

Another important link between Gen Z artists is the desire to foreground personal perspectives and explore their own subjectivities in their photographs, with subjects such as body positivity and radical inclusivity taking centre stage. Using fluid and multi-dimensional ways of representing lived experiences, we can see this in the way gender expression is deconstructed in the work of artists like Yushi Li; in the explorations of queerness and its censorship by artists including Guanyu Xu; in the postcolonialist studies of artists such as Farah Al Qasimi; and in explorations of mental health by photographers like Arielle Bobb-Willis. The impact of the Internet upon consciousness is drawn upon often too, with photographers such as Alina Maria Frieske making work that probes how information is shared online, and how digital techniques can bring pictures alive.

Last year, the New York Post reported that Gen Z have now become the world’s largest generation, constituting 32 percent of the global population. That’s around 2.47 billion of the 7.7 billion people on Earth. This makes them a huge slice of the population for brands and corporations to be marketing themselves towards. Gen Z knows this and they’re wise to the tricks of the trade. They advocate that if they are creating works with messages of empowerment and inclusivity, then brands should be following suit. There’s a lot to be learned from the way Gen Z imagines our future(s), but perhaps the most important lesson of all is how impactful it can be to view both art and identity as realms of possibility, fluidity and discovery – forever in states of becoming – as well as how important photography can be in helping us to merge and celebrate the two.

Joanna Cresswell

ロンドンを拠点とするライター、編集者、キュレーター。写真とカルチャーを専門とし、多数の媒体に寄稿するほか、これまでに『Unseen Magazine 』『Self Publish, Be Happy: A DIY Photobook Manual and Manifesto』『Photobook Review』などの編集も手がけている。