Taro Karibe has made his way to disaster zones and warzones – photographing them as a photojournalist – while consecutively pursuing his own personal works of photography. Yet as he continued with these endeavors, Karibe remarks that he began to feel “the limitations of journalism as a technique.” He takes part in this year’s “LUMIX MEETS BEYOND 2020 BY JAPANESE PHOTOGRAPHERS #6,” where he exhibits a newly-photographed series of his works. Within them, we see him embark on a new frontier of expression: one in which he depicts glitched images as displayed on a television screen. Within the realm of contemporary photography, the lines dividing art and journalism appear in a state of dissolution; with experiences spanning over both realms, we spoke with Karibe about conflicts that the news lacks the power to portray, as well as his long-harbored doubts surrounding its power as a form of expression.

Interview=Eisaku Sakai

Photo=Dustin Thierry

―It’s my understanding that you originally take photographs as a photojournalist. What led you onto the path of journalism?

I had wanted to become a painter in high school, but I felt that it wasn’t right for me; I thought myself unable to create 1 from 0, or substance from nothingness. But in that regard, I realized that photography is simple – all one has to do is press the shutter button. After realizing that, I started thinking about applying to art school. But considering my colorblindness and the difficulty I have in distinguishing between minor differences in color, I decided to give up on the idea.

It was just around the time that I felt the path to photography close; I had been looking around at sites online, and I happened to stumble upon a website with an archive of wartime footage. I watched a video of someone receiving the death penalty there, unedited. It was appalling. I knew that I couldn’t be a photographer, but all the while I felt that I had to find some way for me to come face to face with what’s happening in the world; the idea to pursue journalism began to dawn upon me then. I wasn’t sure how to proceed along that line of study, so I decided to major in psychology, which was my second area of interest.

―Were you studying journalism concurrently with majoring in psychology in college?

Yes. But as I was learning about the theories behind social problems there, I felt like there was a sense of reality that was missing. The sensation that I was alive in this moment was very faint; I wasn’t assured that I was really making any kinds of decisions for myself, while I experienced death as a concept that felt removed and impersonal to me. I wanted to understand what was going on in the real world and what it means to be alive. This all led me to take a leave of absence from school and travel to South Africa to work for an NGO.

―Was there a shift in your perception of reality after going to South Africa?

There was. One time I had been riding a night bus, and the bus fell off of a cliff. Our bus had collided with a large container-car that was coming from the oncoming lane; I had at been sitting in the very front row when it happened, which was the only part of the bus with seatbelts. I happened to have my seatbelt fastened so the impact didn’t throw me out of the bus, and very fortunately I came out of the incident unscathed. That very minor slip in fate helped instill in me the sense that I’m really alive, that there is a sense of reality to the events of the world.

―There may be nothing that will make you feel more alive than that.

When I got out of the bus with my life somehow intact, I looked up at the night sky and the stars were absolutely stunning. It was a road in the middle of nowhere, and the sky unfolded like something that you would see in a planetarium. I was astounded and thankful to be alive – and at the same time, I found myself thinking that I didn’t want to die. My ways of thinking began to change; I wanted set out to achieve what I wanted to do before I die, which worked as a catalyst for me to pursue photography.

―Was it from that point on that you began moving into photojournalism?

I didn’t think that I would be able to become a photojournalist right away, so I started working at a bank with the intention of undergoing a spiritual training period of sorts. Across a span of about three-to-five-years, I wanted to get a glimpse of the world from a financial or economic perspective. I decided to quit my job and began working as a freelance photographer when the angle in which I perceived the world began to solidify.

―Were the personal works that you made consecutively with your journalism work made from a journalistic perspective as well?

Not necessarily. Generally speaking, I’m involved in two types of photography; the first encompasses my work as a photojournalist, where I visit and photograph disaster sites and other places as a form of news. In the second, I depict my own abstract thoughts by way of photograph. The first is photography that depicts the world as it happens around me, while the second serves to explain what is happening in my own head.

―Though in looking at your past works, it seems as if you consistently employ a journalistic, documentarian approach.

Yes, well truthfully that’s something I feel conflicted about. I have a work collection entitled “Letters to You”, in which I used a Polaroid camera to document the Rohingya – a people from the west reaches of Myanmar that have migrated into Bangladesh as refugees. As I was working on the series, I began to get the feeling that techniques journalistic and documentarian in nature may not resonate with me anymore. While of course those techniques play an important role in society, I realized that what I really want to express is whatever is happening inside of my own mind.

―Would you delve into further detail on the “limitations” of those techniques?

When I first released “Letters to You,” people saw my background and conceived me to be a social activist – and more so than I predicted, people saw my work solely as a piece that extolls social justice. And it is true that those depicted within the photographs are refugees, and the work does tell a poignant narrative about their missing families. People are free to conceive my work as they wish, but I felt an incongruity with how the work was coming across: one I wasn’t able to simply dismiss or ignore. I felt as if I hadn’t been able to portray other important points within the narrative.

In 2016, I went to photograph scenes of the aftermath of the Kumamoto Earthquake as part of work for a news agency; and while I felt a sense of purpose in portraying what I witnessed to the world, photographs like those tend to be swept up and displaced by another topic of discussion. It’s hard to develop any sort of discourse from them that is not extremely concrete. Personally, I am the kind of person who likes to think about things on a higher dimension: on things that are more abstract. I think I felt a disconnect with the aspect of universality of interpretation that exists within that form of expression.

―In the case of journalism, I think there is a power added to the photographs precisely because of their specificity and their context – but it seems as if there was a conflict that arose between these points and your own expression. What themes did you cover in “Letters to You?”

Of course, the pretext here is that it is about depicting those who are in suffering, but I also took the photographs in hopes of discovering more about the perceptions of the viewers. Most refugees in the photos are people whom the viewers do not know personally, and I wanted to know what is it that these people need to be truly present and alive. I was curious about the differences that exist between myself and others.

―So, you trained your focus on perception. In looking back on your works, it feels that “INCIDENTS,” which utilizes glitches in its expression, was a turning point for you. You move from the concrete to the abstract.

It was an attempt to project what was in my mind into the outside world. With the glitches, I think it was that I had switched to a technique that allowed me to purely express what was on the inside, without relying on the concrete.

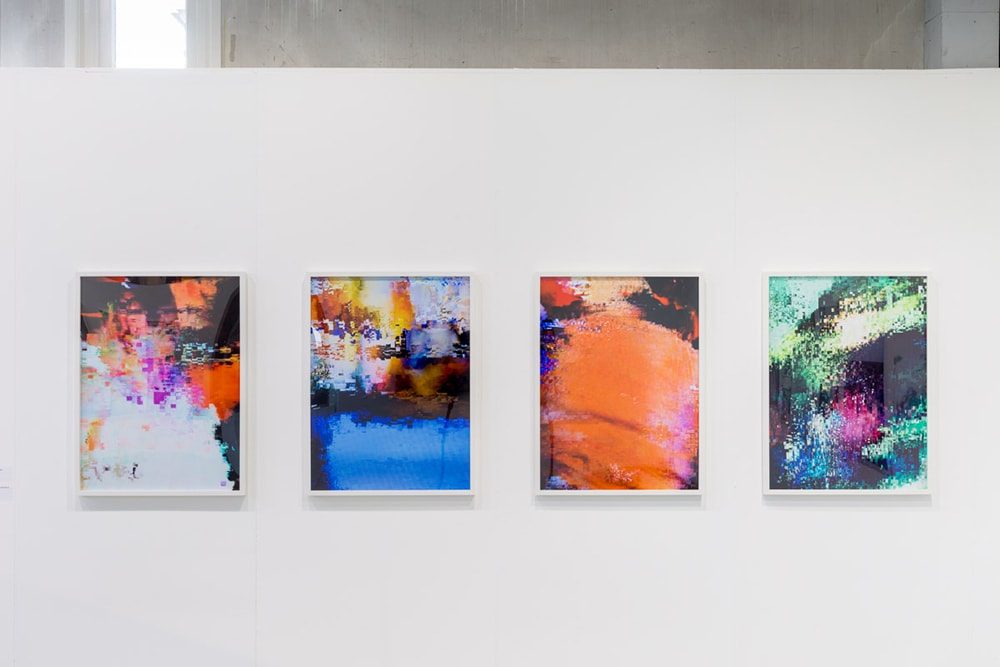

LUMIX MEETS BEYOND 2020 BY JAPANESE PHOTOGRAPHERS #6 in Amsterdam (Photographs by Shinji Otani)

―You’ve photographed glitches of television screens for your new works exhibited at the BEYOND 2020 exhibition as well. Was there a difference in creating these as opposed to taking photographs outside in the field?

Of course there is a difference in the sense of responsibility I have towards the subjects and the subject matter of my works. But whether it be photographing refugees or the screen of a television, I feel the same degree of sincerity towards the subject – and in that way there may not be much of a difference between the two within me. The shooting process for this series was laborious. I had to physically work to distort the reception of a television set myself, but a glitch may only appear once out of 100 attempts. And for only a moment, no less. I had to dedicate an entirety of 10 days towards it, and I was only able to get about 12 shots across that span of time.

―That sounds like an ordeal… in photographing the television screens, did you yourself find a sense of reality in that process? Was there a shift in your perception of the shooting process?

I had to switch through channels as television programs were displaying on screen, which meant that I had no control or foresight over what would appear next. It was an experience close to taking street snaps: like I was constantly waiting for something to happen. I felt a sense of reality and aliveness in the sense that I was surprised by the elements that I weren’t expecting to appear.

The Talk Event at the LUMIX MEETS BEYOND 2020 BY JAPANESE PHOTOGRAPHERS #6 Exhibition in Amsterdam

―I find myself asking this again, but starting from your time in South Africa and on towards your experience with the Rohingya and leading into the present, did you notice a shift in your perception of reality?

There hasn’t been much of a shift. For example, my experience of the accident in South Africa was traumatic. But when thinking back on my experience, I realize that it was the minute details of the experience that allowed me to feel that I was connected to reality: the sensation of glass shards clinking on my skin, the smoke flowing through my hair. Reality exists in the minor details, and in the information that people often consider to be a waste – things that can’t be told by the news. That was what I wanted to touch upon with the works of the Rohingya. With glitches as well – they are figments that we remove, things dismissed as erroneous.

ーThat’s true. Despite the change in methodology, there is no change in how the individual yearns for an earnest sense of reality. How about the viewers and the audience? Did you notice any reactions from them?

None of the photographs within the glitch series depict a specific image or subject within – originally, they are images from television programs, but I rotate and dramatically trim them so that there are no traces of the original contexts within the images. A friend of mine saw one of the photographs and said that it looked like a castle. It doesn’t appear that way to me so I have a hard time relating; but in the end, that is reality as my friend sees it, and that is how things have become in this age of human society. The photographs appear almost as a sort of Rorschach test, one which projects what the viewer wants to see.

―Reality takes different forms. It seems the works function as an entrance way, where each viewer is able to participate in their own way by way of their own perspective.

I make works in hopes of comprehending what I do not understand, but there are limitations to what I can achieve when it is just me by myself. So in that way, I enlist the help of viewers in furthering my own understanding… and I suppose it sounds self-serving to say it like that, but there are conundrums that we cannot solve. And it’s precisely because many people in society are facing the same doubts that I believe that this question – What is reality? – is something that I want to think about with everyone.

Taro Karibe

Born in Aichi, 1988. Karibe graduated with a Bachelor of Psychology at Nanzan University in 2012. While at university, he studied in the U.K. and Johannesburg, working for a NGO controlling epidemics in South Africa. After working a few years in corporate banking, he became a freelance photographer. His practice explores themes of the uncertainty of the boundary between the self and the other and the contingency of the world. He has earned both national and international acclaim for his work, which has appeared in numerous magazines, including the New York Times and the Washington Post.

https://www.tarokaribe.com/